Chicago's development process has created segregated and unequal neighborhoods. The city needs to change its way of doing business to address historic and structural inequities

Image courtesy Getty Images via Crain's Chicago Business

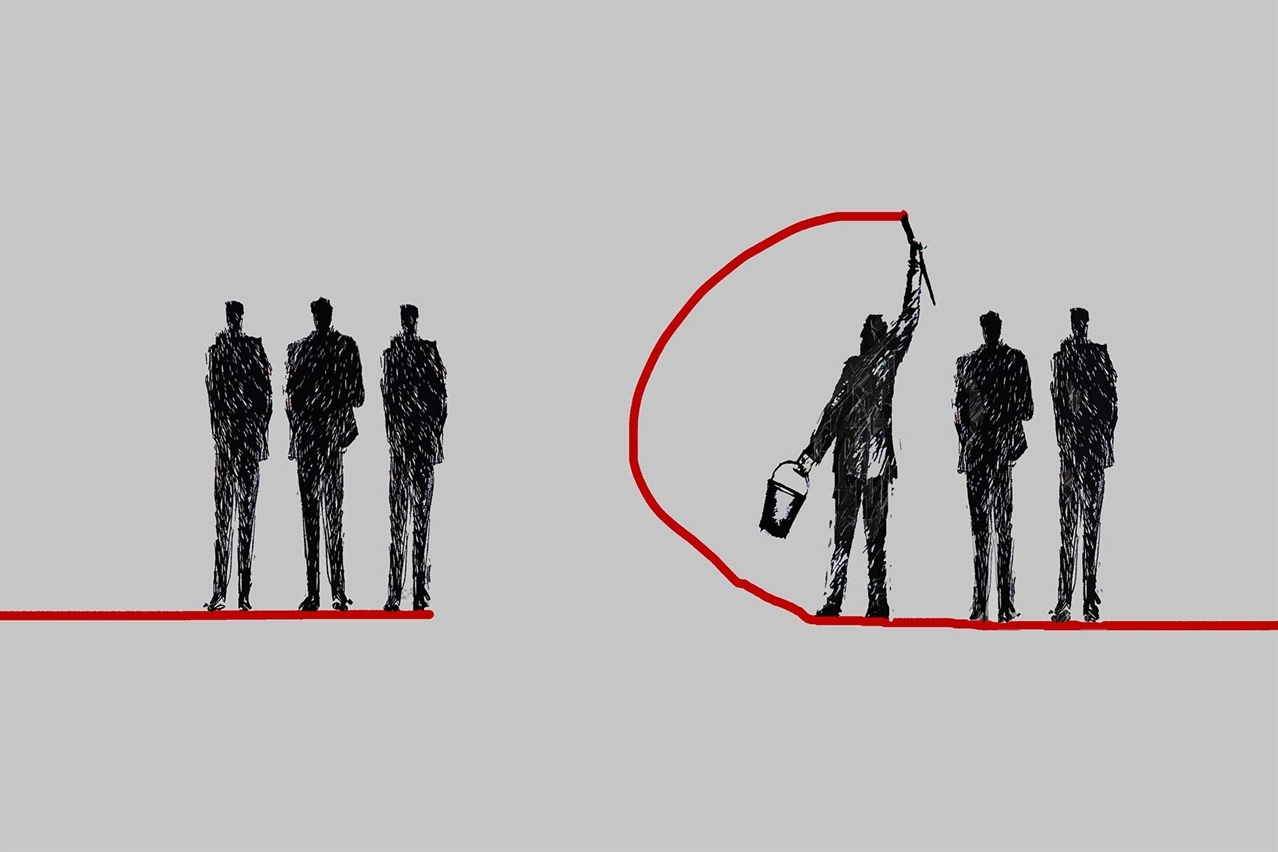

A colleague recently asked if I could diagram the process through which commercial and residential development is approved in Chicago. It stopped me in my tracks.

This casual question reminded me how much time and effort is spent on the unwritten rituals of "kissing the aldermanic ring" and brokering support from power players, and how little time is spent empowering local voices to shape a project so residents get what is wanted and needed.

Regardless of the development type (affordable housing, retail, etc.), if achieving racial equity in our housing and community development is a priority, we need to change the way we do business.

Over generations, development policies and practices have erected barricades in and around Chicago, leading to a region where people live separately by race and income. The long-term result: limited wealth-building opportunities for people of color and sustained disinvestment in black and brown neighborhoods. Attempting to bring parity to community and economic development cannot be done without acknowledging that the system is built on racial exclusion. Even if we want to do better, until we create policies that are corrective and restorative, we simply won't.

To produce better outcomes, the development approval process needs a reset—one that accounts for historic and structural inequities, balances data with local narratives, and weighs who benefits and who is most burdened. Starting with these questions will guide a framework for how and where we make investments in communities that have been systematically excluded.

One place to look for inspiration is Upper Harbor Terminal, a 48-acre riverfront development in Minneapolis that has publicly committed to "bake in" racial equity. The city acknowledged its history of segregating black residents and is building local voices into the planning and decision-making to ensure community benefit.

Closer to home, advocacy organizations Grassroots Collaborative and Raise Your Hand for Illinois Public Education filed a lawsuit challenging who benefits from tax-increment financing dollars that could force the re-examination of whether the process, as it has been applied in Chicago, is racially discriminatory. And while we applaud efforts by some in the development industry to increase diversity on the construction and supplier side, by incubating small businesses and actively hiring minority-owned firms, much more is needed.

Successful equitable development requires a shift in industry culture and practice. Talking with residents, not at them. Inclusive planning and ongoing evaluation to measure outcomes. Engaging in the hard work to incorporate affordable housing in high-cost areas. Returns on investments that benefit both shareholders and community members.

Will these interventions move the needle on long-term results? Many factors influence the ultimate success or failure of a project. But the results of our status quo are well documented: Revitalization efforts have created and sustained neighborhoods that are separate and unequal. What we know is that starting from an equity framework has shared advantages. The Metropolitan Planning Council's "Cost of Segregation" study quantifies that narrowing equity gaps increases overall economic returns as well as social benefit.

Mapping out a process for racially equitable development is a formidable task. It starts with naming racial equity as an outcome with intentionality to achieve it, committing to a process of authentic engagement and building a deep community of practitioners—all of us.