Low levels of grocery store access, high reliance on public transportation, and unequal broadband adoption mean that, for some Chicago neighborhoods, food during the pandemic is not available in a quick walk or at the push of a button

photo courtesy of Flickr user kurt

Where have you traveled within the last week? Chances are, the grocery store. If not, are you getting food delivered? Eating is one of the fundamental aspects of life that unites us all, but for many of us, access is not equal or easy.

Chicago hosts no grocery store within walking distance for many of its residents. Simple solutions to this problem would be for people to drive, take public transportation, or get their food delivered, by way of apps like Shipt or Instacart. But these simple fixes are complicated by a number of factors, especially during a pandemic. Based on the latest five-year estimates from the American Community Survey data, there are an estimated 26.78 percent of occupied housing units in Chicago for which no vehicles are available. In other words, residents in over one-quarter of Chicago homes have no access to a vehicle. But public transportation poses its own risks, as communal travel can potentially increase your risk for exposure to the novel coronavirus as you naturally come into contact with more people. What’s more, some residents who live in food deserts, areas without easy access to health-promoting food options, must take multiple forms of public transportation for up to three hours just to grocery shop. This was unacceptable before the pandemic and is now compounding residents’ hardships during this crisis.

For many, getting food delivered is also not an option: Some areas may have limited providers or service based on their distance from a store, and SNAP benefits currently cannot be used for grocery delivery. Lack of internet service is also a hurdle. During this pandemic, the internet has become the backbone for social connection and essential services. It has become a lifeline. But, there is a lack of equitable broadband adoption across the city. (For the purpose of this post, “adoption” refers to the household presence of a subscription to any type of broadband internet service provision [cellular, cable, fiber optic, etc.].) Some Chicago community areas have nearly 100 percent adoption at the household level, while the residents of other community areas struggle to afford plans. Many internet service providers, like Comcast, offer affordable programs to fill gaps in adoption, but these programs do not address all the existing holes.

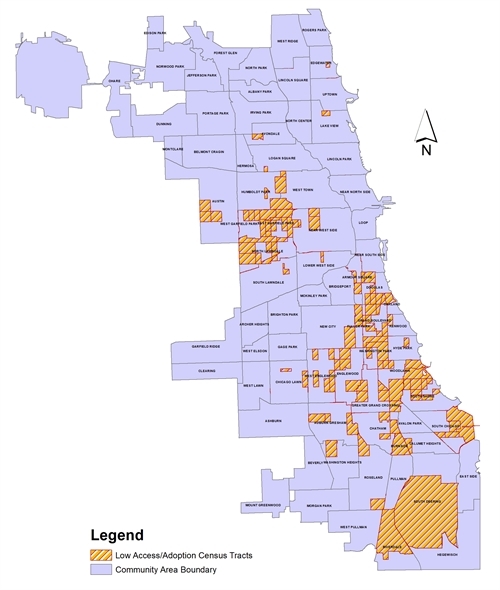

So what happens when we look holistically at the factors preventing some Chicagoans from easily accessing food during the pandemic? Which areas are most affected by a lack of access to groceries, cars, and internet? When we at MPC mapped grocery store distributions across the city to determine access[1] as well as rates of broadband internet adoption[2] combined, we observed that just under 40 percent of the city’s census tracts fell below the average level of access/adoption in terms of both quality of life indicators. When we examined a third metric—household vehicle accessibility[3]—we observed that more than 18 percent of the city’s census tracts fell below the average on all three metrics; these tracts are displayed on the map below. Notably, nearly all of these tracts are concentrated in communities of color on the South and West sides of the city, the vast number in majority-black communities.

It should be noted that access and adoption are based upon the following tract-level benchmarks: an average of .29 grocery stores per census tract in Chicago; an average of 61.1 percent of households per tract with a subscription to any broadband internet provision; and, finally, an average of 1.06 vehicles per household per Chicago census tract.

Low levels of grocery store access, high reliance on public transportation, and unequal broadband adoption are three factors that all combine in community areas like Riverdale. The novel coronavirus is shining light on planning and development challenges that burden some communities more than others, making the simple act of grocery shopping increasingly difficult.

Riverdale has been described as a “toxic donut”: a neighborhood surrounded by industrial land uses and lacking both physical infrastructure and community amenities. Its challenges are well documented, perhaps best summed up by resident and community activist Deloris Lucas in a 2019 Chicago Tribune article, “We’re truly in a food desert, a financial desert, a transportation desert, a sidewalk desert, and a whole lot of other deserts.” Planning Studies have confirmed residents’ challenges in getting around their neighborhood and the city and its lack of amenities. Approximately 40 percent of residents in Riverdale lack access to a motor vehicle and rely on public transportation. Many people’s closest grocery store is a Walmart that can take six to eight times longer to travel to on transit rather than by car[4]. The coronavirus is exacerbating this situation and making it harder for residents to get the essential items they need. Organizations like TCA Health are working to fill this gap and ensure that populations most at risk from the novel coronavirus, like seniors, still have food and other essential supplies like toiletries and toilet paper. They are delivering Care Packages of nonperishable items to older residents in need. Many of these items are sponsored by staff of TCA Health themselves. Riverdale is just one example of family and community networks coming together to offer support during this time, but residents in these communities should also be able to rely on basic city amenities, like internet broadband and grocery stores.

As the Chicago region begins to emerge from this global pandemic and focuses on building greater resilience into our economic and social fabrics, we must consider how we are supporting communities. Lack of grocery stores and inadequate public transportation infrastructure were not created by the coronavirus. They were created by planning policies that for the past twenty years prioritized downtown investment and growth without a sustained focus on community areas that still do not have basic, essential developments and food access. All Chicagoans should be able to safely and quickly access food, now and in less-challenging times.

The above map was produced based upon the intersection of city census tracts that fell below:

[1] the city average of grocery stores per census tract; calculated through geocoding the Chicago Data Portal’s July 2018 grocery store distribution list

[2] the average percentage of households per tract with a subscription to any type of broadband internet service; 2014-2018 ACT estimates

[3] the average number of vehicles per household per tract (where a vehicle can mean a car, van, etc.; 2014-2018 ACS estimates

[4] Data from the Riverdale Community Area Multimodal Transportation Plan, pg 28