Mapping the impact of racism and disinvestment

Flickr user MBA Photography

Intersection in Lakeview, part of the 44th ward—one of several north side Chicago wards where less than 5% of housing units are affordable

MPC Vice President Marisa Novara advised and contributed to this work.

In this series, the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) will explore patterns of affordable housing distribution across the city of Chicago, and the various factors and actors that influence these patterns.

Even 50 years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act, NIMBYism remains a strong force against affordable housing.

Modern “Not In My Back Yard” rhetoric ranges from overt refrains (“No Section 8!”) to more veiled statements (“We’re opposed to overcrowded schools, not people”). No matter the chant, the ability of residents to reject affordable housing in their neighborhoods is in large part enabled by aldermanic prerogative. As reported earlier this year by the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance, this power to delay or block new housing developments has been historically and disproportionately used by aldermen in the city’s affluent, majority-white wards to maintain status quo racial compositions, typically in response to pressure from their constituents.

In new findings released by the Metropolitan Planning Council using third-part data and analysis, we map the racial inequities in the development and availability of affordable housing across the city.

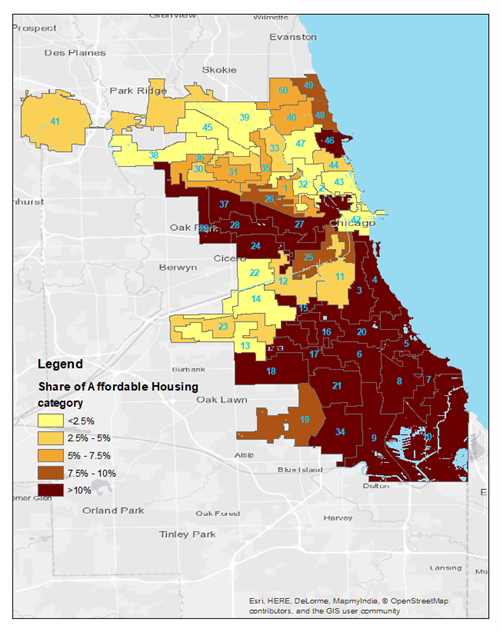

In partnership with the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance, MPC worked with a third-party analysis firm earlier this year to visualize the distribution of long-term subsidized units including permanent multifamily housing, rental subsidy, and Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) units across the city. Looking at the share that affordable units comprise of all rental units within that ward or tract, it is easy to identify where affordable housing is most abundant, and where it is most scarce. The data serves as a jumping off point for policy discussions around access to housing across Chicago, and for exploration of the policy implications of utilizing a 10 percent affordable housing threshold when evaluating development decisions—that is, taking a different approach to evaluating development proposals in wards where affordable units make up less than 10 percent of the rental housing stock. While we know that 10 percent is an arbitrary benchmark and not a large share, this threshold is based on the statewide Affordable Housing Planning and Appeals Act, and served as a starting point for the analysis.

In Chicago’s whitest and wealthiest wards there is less than 2.5 percent affordable rental housing

Metropolitan Planning Council, based on third-party analysis

Share of affordable housing units by ward in the city of Chicago

Wards that fall into the “less than 2.5 percent” category are much whiter and wealthier than their “over 10 percent” counterparts. Using the most recent estimates from the American Community Survey, we found that median household income (MHI) averaged across the 11 lowest-share wards is close to $80,000 in 2018 dollars, and on average, white residents make up 54 percent of the wards’ population composition. Across the 21 wards with the highest share of affordable units, the average median household income is almost half at just over $43,000, and white residents make up just 11 percent of the wards’ population composition, on average. As shown in Map 1, the clustering of affordability by geography is unmistakable. Affordable units make up less than 2.5 percent of all occupied rental units in 11 of the city’s wards, almost all of which are located on the North and Northwest Sides (see areas in lightest yellow). In contrast, the 21 wards that have over 10 percent (in dark red) are all located on the South and West Sides, as well as Ward 46 on the North Side.

Another distinction between these two categories is the balance between renters versus owners. Across the 21 wards that have over 10 percent in affordable housing stock, the average renter versus owner composition is 55 versus 42 percent. These numbers essentially flip when we examine the balance across the 11 wards that have less than 2.5 percent affordable housing stock (43 vs. 54 percent). Again, this is not by accident.

Dating back to racially restrictive covenants in the early 1900s, white property owners all across the U.S. were successful in closing off entire neighborhoods to black residents. Though these covenants were eventually deemed non-binding in a 1948 Supreme Court decision, they fueled notions that live on today regarding the “mandate” of homeowners to shape their surroundings, often overlooking the needs and desires of current and prospective renters in the process.

Housing Choice Voucher units disproportionately contribute to affordability in “high affordability” wards

Metropolitan Planning Council, based on third-party analysis

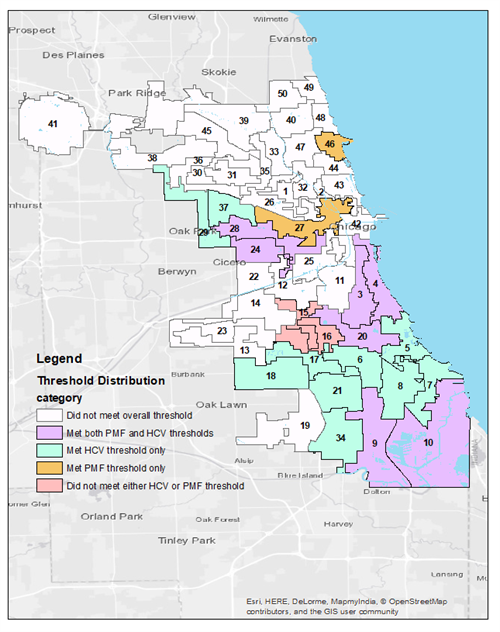

Distribution of affordable housing by unit type for wards that meet the ten percent affordability threshold

In order to understand how wards that meet the “over 10 percent” threshold manage to do so, we also dove into distribution of affordability by unit type. On the map on the right, we display a breakdown of wards, distinguishing between those that meet the overall 10 percent affordability threshold in color versus those that do not in white. Further, we break out wards according to whether or not they meet the 10 percent threshold by ward when only counting permanent multifamily units or HCV units.

Of the 21 wards that meet the overall threshold, only two—the 27th and 46th wards, in yellow—manage to do so through a reliance on permanent multifamily units primarily. In future posts, we will delve into how each has managed to do so.

The majority of wards, instead, rely on a greater than average share of HCV units (see wards in green and purple). Considering that the Housing Choice Voucher program was first created as a means to open up mobility and choices for renters who had previously been tied to public housing units only, today’s dense clustering of HCV units across the city’s South and West Sides is yet another indication that individual and systemic racism is still shaping where people can live. Here’s the individual part: despite it being against the law, landlords often still refuse to rent to voucher holders. And now here’s the systemic part: allowable rents set by the voucher program are often too low for voucher recipients to even access many parts of the city.

A path forward: toward an equitable distribution of affordable housing

As advanced in our policy roadmap—Our Equitable Future—we envision a Chicago where affordable housing proposals in neighborhoods that lack it can’t be rejected simply because constituents don’t want those developments. In this future, all communities across Chicago would contribute to the city’s affordable housing needs, not only some. While we believe there is a role for local input, that role should be in the form of how affordable housing is delivered, not if.

One major step toward that future is the recent filing of a federal civil rights complaint by the Shriver National Center on Poverty Law to limit the very practice of aldermanic prerogative. As noted by the Chicago Sun-Times, “aldermen often hide behind local zoning advisory councils created for the purpose of acting as buffers for such decisions, while residents often couch their objections in terms of a project’s density, height, congestion and traffic to mask their racial animus.”

Another hopeful step forward is the Affordable Housing Equity Ordinance, a piece of local legislation that Alderman Ameya Pawar introduced in July, along with 26 co-sponsors. This ordinance stipulates that in wards that have less than 10 percent affordable rental units, developments with affordable units cannot be rejected or delayed indefinitely for non-fact-based reasons.

What are non-fact-based reasons? Statements like “I don’t like tall buildings,” or, “I like our semi-suburban feel.”

Measures that would further strengthen the city’s commitment to the equitable distribution of affordable housing could include eliminating the requirement of an aldermanic letter of support for city funds for affordable units, and requiring that all mandated affordable units through the city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance be built and not bought out, whether on-site or a combination of on- and off-site.

While our advocacy to limit aldermanic control over housing decisions is neither radical nor ambitious enough, it is one avenue to address the structures that reinforce our separation. Look to future posts in this series where we will unpack how far we still have to go, which will include an examination of some of the most commonly heard objections to affordable housing, as well as case studies across our city and region.

For Chicago residents, the injustices of the past are inescapable: the deeply rooted racist policies of federal, state, and local government enabled decades of chronic disinvestment in non-white neighborhoods of the city. These investment patterns have shaped the landscape of schools, parks, and other desirable amenities in such a way that our city’s whitest neighborhoods are often held up as the most certain guarantees of upward economic mobility. For residents of color, this often means that living in proximity to the “best” _____ (insert amenity of your choice), also means living in proximity to whiteness. Many residents, however, are shut out of even considering these resource-rich areas as possible living options due in part to their lack of affordable housing.

To be clear: residents of color shouldn’t have to move to the city’s most heavily invested—and also whitest—neighborhoods in order to attain upward mobility. In order to right the wrongs of structural racism and disinvestment, we must listen to the needs of residents in areas that have been historically overlooked—largely, communities on the South and West Sides—and respond in a way so that those residents can successfully move up the economic ladder right where they are. At the same time, the option to live in resource-rich areas should be available for those that want it. And this latter part of the conversation can’t be had without a critical look at our housing options.

Additional news coverage

Listen to an interview between Shehara Waas and Marisa Novara with WBEZ's Melba Lara.

MPC’s Blogs and Data Points on community development and equity issues such as this are made possible in part by the Chicago Community Trust – Seale Fund, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Field Foundation of Illinois, the Bowman Lingle Charitable Trust, the Conant Family Foundation, and individual donors.