A chat with Strong Towns Founder Chuck Marohn

On April 16, MPC hosted a conversation with Charles Marohn, president and co-founder of Strong Towns, a nationally recognized non-profit media organization working to shape the perspectives on growth, development, and the future of cities. He discussed his philosophy on planning, development, and municipal finance as reflected in his recent book, Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity. You can watch the entire discussion here and read about some of the highlights below.

Make no little plans

Daniel Burnham, Chicago’s famous visionary, gave the world one of its greatest aspirational ideas: “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood.” It’s a powerful sentiment, but it has dramatically different implications today than when Burnham said it 110 years ago. As Marohn explained, visionary projects of colossal proportion took a colossal amount of time to complete. Major public works took decades, even centuries, with each subsequent generation learning from and building on lessons from the past. That all changed after World War II. In the United States, our ability to access capital and extract resources had reached frenzied heights that made rapid transformation possible. Post-war development became a “cultural assembly line” where everything was standardized for maximum efficiency and profitability. As a result, we radically altered an entire continent in a very short period of time. This generated tremendous wealth, but it did not – and has not – translate to financially stable places.

No quick way to strong towns

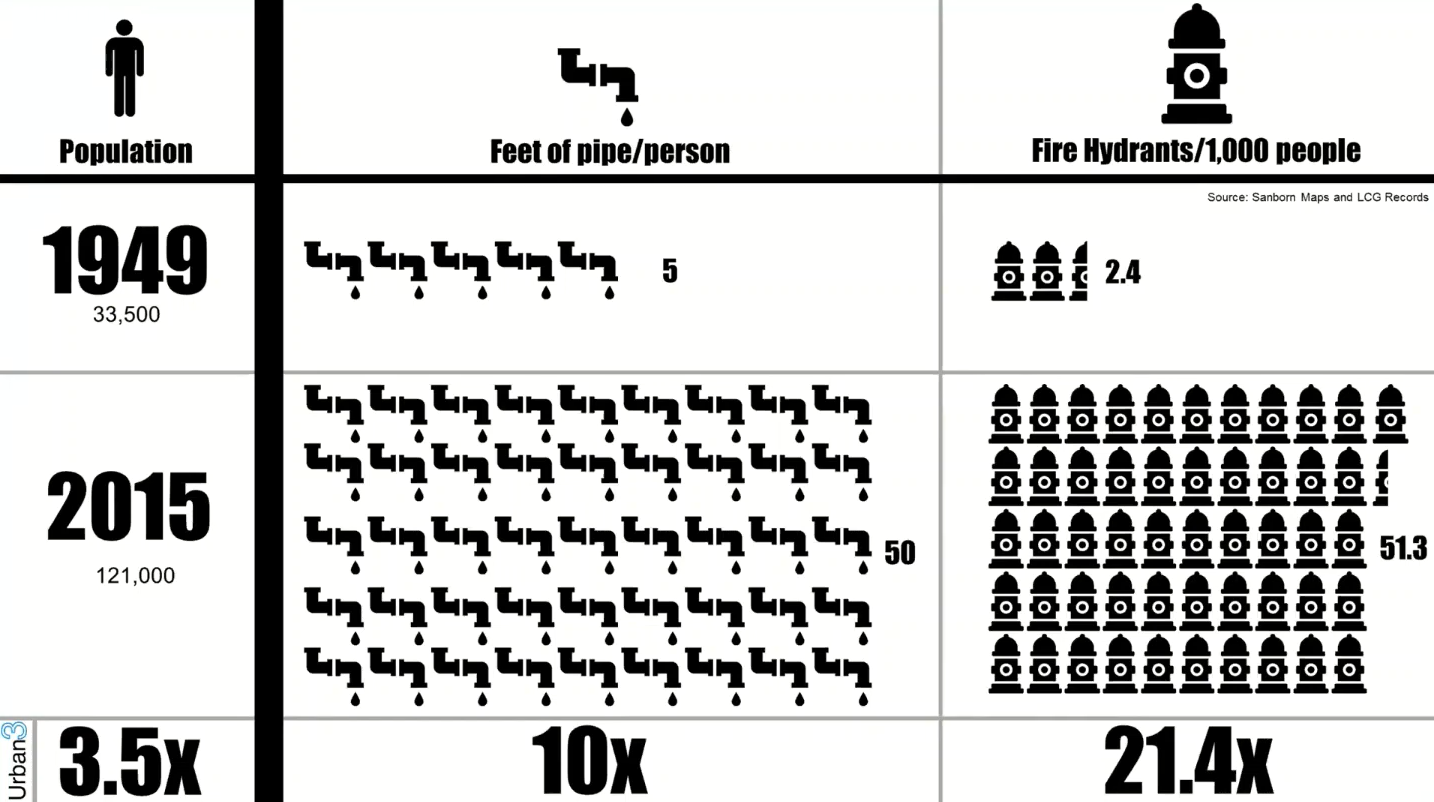

Marohn used several examples to explain how rapid growth is actually quite fragile, and ultimately unsustainable. First, he discussed the experience of Lafayette, LA in the post-war years. The graphic below shows how the population of Lafayette nearly quadrupled from 1949 to 2015. But in that same amount of time, the amount of municipal water pipes needed increased tenfold. The number of fire hydrants needed to safely provide fire protection increased by more than 20 times. Why did public infrastructure grow at a much higher rate than the population? It has to do with the way Lafayette, and virtually every other American city, developed after WWII. We spread out very quickly. We began living at much lower densities, meaning that we required much more infrastructure per person.

The growth of public infrastructure in Lafayette, LA has far outpaced population growth. Courtesy of Strong Towns.

Putting the environmental impacts of sprawl aside, this wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing if household wealth was growing at a similar pace. But it hasn’t – not even close. And herein lies the problem. Local government, as Marohn explained, is nothing more than a tool for our collective action. Municipal services and local infrastructure are what enable us to conduct our business and live our lives. To make sense, those public investments need to be backed up by financially productive places. Marohn used an example from his hometown of Brainerd, MN to illustrate how post-war development isn’t meeting that need.

Two adjacent blocks in Brainerd, MN with different development styles have very different levels of financial productivity. Courtesy of Strong Towns.

The graphic above shows two adjacent city blocks in Brainerd. The one on the left features a pre-war style of development: small lots with many businesses and little to no parking. In another time and place, this style would have allowed for incremental increases in intensity of use as demand grew. Instead, as Marohn put it, it was essentially frozen in time and abandoned. Today, it looks shabby and has a number of vacancies. The block on the right once looked nearly identical, but the previous development was razed and replaced with a modern fast food restaurant with a drive thru and surface parking. It even has new landscaping and modern sidewalks. To most people the lot on the right would seem more prosperous. But in fact, it’s much less productive. The dollar figures shown reflect the net financial productivity of each block for the City of Brainerd. They show the difference between the revenues paid to the city and the cost of public services provided.

The productivity paradox

The example above illustrates a paradox in financial productivity. When you analyze the developments that are most financially productive, they are always the denser, walkable areas that were built incrementally over a long period of time. The paradox is that these developments are very frequently in some of the poorest parts of a community. It seems counterintuitive that poorer areas would the great stores of wealth and productivity for a city, but as Marohn explained, they end up subsidizing the wealthy areas in the long run. This isn’t apparent if you only look at the immediate future. Local governments frequently believe that new development at the edge is how you will pay for things. After all, these are the areas with a positive cash flow. They have immediate access to private capital and can build quickly. But in the long run, they are a net drain. They cannot create enough value to pay for the costs of providing the infrastructure and services they need, miles of roads that serve relatively few houses, and many miles of water and sewer pipes.

The future of cities and suburbs

If we haven’t been building financially sustainable places, and have neglected the only parts of our communities that are productive, what does that mean for the future of our cities? Marohn returned to the experience of Lafayette, LA. The median municipal tax burden for a household in Lafayette is $1,500 a year. To actually pay for the full long-term costs of public infrastructure and services, that bill would need to be $9,000. For many reasons, that is not ever going to happen. Most cities haven’t come to reckon with this yet. They are still chasing short-term growth, putting off major projects and deferring maintenance. But one example does exist: Detroit. The Motor City was the archetype of post-war development. Like the assembly lines of Ford and General Motors, they were the first to perfect the urban growth machine. They were also the first to have the bill come due. Detroit’s steady retreat is well-documented, but the city will never wholly disappear. In the past few decades, in an incremental way reminiscent of pre-war city-building, certain parts of the city have begun to thicken up, while vast expanses continue to be abandoned. This, Marohn stated, is a natural byproduct of the way we’ve built things.

So what’s the path forward? Marohn recommends a humble approach. Focus on maintaining what you have, and investing incrementally in high productivity areas. It’s critical to remember that high productivity does not mean high wealth. In fact, it’s frequently the opposite. Create a system that can adapt and evolve, then see where the successful places emerge. Then, build on those places in an incremental way. In the context of the COVID-19 crisis and the reality of dramatically shrinking local revenue, this is a rare opportunity for us to rethink the way structures and mechanisms we use to build, grow and invest. We shouldn’t make little plans, but we should be ready to take little steps.