Preventing displacement in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis

By Miriam Zuk, Diane Limas, Charisma Thapa and Andy Geer

By Miriam Zuk, Diane Limas, Charisma Thapa and Andy Geer - June 29, 2020

The plight of Chicago’s small, two to four-unit buildings, has received research and media attention for nearly a decade, yet little by way of coordinated and comprehensive action. This needs to change. This iconic housing stock has long housed over a third of the city’s working-class residents[1] and has been a crucial source of affordable homes, especially those that include basement apartments that tend to be among the most affordable in the city. Yet Chicago has been losing these affordable homes for nearly a decade due to foreclosure, abandonment, flipping and deconversion. The coronavirus pandemic threatens to accelerate the loss of this crucial affordable housing, with significant displacement consequences for Chicago’s vulnerable renters, low income and households of color, threatening to further widen spatial and racial inequities in our city.

If we care about black and brown families in Chicago’s disinvested as well as gentrifying neighborhoods, we need to protect this housing stock now.

Following the 2008 foreclosure crisis, nearly one third of two- to four-flat buildings in weaker housing market neighborhoods were affected by a foreclosure filing, contributing to mass displacement on the South and West sides and the loss of Chicago’s Black population. The foreclosure crisis and ensuing displacement wave resulted in significant community trauma, neighborhood distress and the staggering loss of wealth in Black communities. While new financing that targeted redevelopment of the 1-4 flat stock in the wake of the 2008 crash helped, the economic impacts of COVID-19 threaten to further destabilize these disinvested communities.

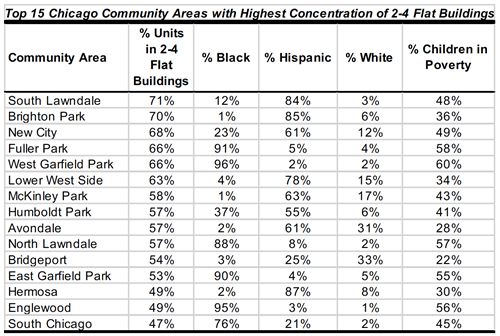

The City of Chicago has declared its commitment to reversing decades of disinvestment and segregation through its Invest South/West initiative, yet stabilizing affordable housing in these areas has yet to officially become part of the effort. To ensure the health, wellbeing and stability of residents in these communities, it’s imperative to ensure they have access to affordable housing. City-wide, nearly 40% of the city’s affordable stock is in buildings with 2-4 units[2] and the neighborhoods with the highest concentration of two- to four-flats are majority black and brown neighborhoods with high poverty rates on the city’s south and west sides.

In gentrifying areas, two- to four-unit buildings are often swept up by speculators, flipped, and/or “deconverted” into single family homes, resulting in a significant decline in the number of affordable units in stronger housing markets. This trend contributed to the significant loss of Latinx households from these desirable neighborhoods. To achieve the diversity, economic mobility and access to opportunity the City’s values, we also need to protect the two-to-four housing stock in stronger, gentrifying markets.

If we want to prevent a displacement cliff, protecting and preserving the two-to-four stock needs to be a pillar of any recovery strategy

To prevent history from repeating itself, it’s important to pay special attention to the two-to-four housing stock in all the COVID-19 recovery efforts. With over half a million people -nearly half of all Chicago renters- living in buildings with 2-4 units, the loss of this stock to foreclosure or speculation could be devastating. Owners of these buildings, especially small mom-and-pop owners, are particularly vulnerable to the economic impacts of COVID-19; with so many job losses, and tenants struggling to pay rent, the loss of 25-50% of their income could push small landlords into financial peril and risk of foreclosure, further threatening the wellbeing of their tenants.

The pandemic has ushered in unprecedented actions from local, state and federal governments to protect tenants and property owners alike. Yet, the precariousness of homes in the two- to four-unit housing stock are not adequately targeted in many of the solutions that are emerging. Preventing widespread displacement from this affordable housing stock deserves a special task force to take a multi-pronged approach considering the following goals and strategies:

Protect Tenants

- Rental assistance: Massive rental assistance is necessary to ensure that households struggling to pay rent due to the economic impacts of COVID-19 can stay in their homes. Special attention is needed to ensure that assistance reaches households in two- to four-unit buildings. This means federal advocacy to get more funding for rental assistance (e.g., passage of the HEROES Act), as well as state and local program design and geographic targeting to cover households in this vital housing stock. It also means ensuring that all renters economically impacted by COVID-19, regardless of immigration, criminal record, and disability status are included.

- Review and strengthen tenant protection ordinances: The City of Chicago enacted the Protecting Tenants in Foreclosed Rental Property Ordinance, also known as the Keep Chicago Renting Ordinance (KCRO), in response to the effects of the mortgage foreclosure crisis on renters. A review and strengthening of the ordinance in preparation for a spike in foreclosures is necessary, including evaluating the efficacy of noticing procedures and relocation fees, among other elements of the ordinance. Protections for renters in non-foreclosed units are also needed to ensure that people aren’t displaced in a wave of speculation. This means passage of a Just/Good Cause for Evictions ordinance that would restrict the reasons landlords can evict renters while also requiring relocation assistance.

- Explore Community First Right of Refusal: Local ordinances like D.C.’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act or San Francisco’s Community Opportunity to Purchase Act, give qualified non-profit organizations the right of first offer and/or the refusal to purchase eligible properties on the market to prevent tenant displacement and create long-term affordability. The feasibility of such policies to preserve two- to four-flats in the Chicago area should be evaluated.

Support Landlords

- Forbearance for All with Favorable Terms: Small landlords of the two- to four-unit stock are especially vulnerable to lost rent and many may not be not receiving the forbearance offered by federally-backed mortgages. Consistent terms for all lenders, such as those recommended in NHS’ Uniform Forbearance campaign, are needed, including prohibiting lump sum repayments, penalties or charges, and reporting to credit agencies, to ensure small landlords are protected.

- Mortgage Relief: Whether we like it or not, owners of this stock will be facing significant risk of foreclosure. It’s important for new mortgage relief programs, like the Illinois Housing Development Authority’s Emergency Mortgage Assistance, to ensure that mortgages on two- to four-flat buildings are eligible and given preference or a set aside, as they will stabilize housing for more families than relief to single family homes. Special consideration to the unique configurations of two- to four-flat buildings, such as units rented with verbal, month to month agreements rather than a lease[3] or inability to make needed repairs[4], are also needed to ensure owners of this stock are adequately covered.

- Outreach and Educate Owners: Extensive outreach is needed to ensure that owners of two- to four-flats know about existing programs and options available to keep their properties. Targeting small owners may require additional outreach efforts in the time of social distancing. Housing counseling centers and local community groups need to be adequately funded to ensure that small owners know about available resources.

Preventing the Loss of this Affordable Housing Stock due to Speculation and Abandonment

- Slow the Speculative Market: America’s speculative pastime is great fodder for reality TV, but it does not serve tenants. Cash and “business” buyers swept up most foreclosed properties after the last crisis, making it impossible for community-minded residents, investors and developers to compete. While it may be challenging to prohibit flipping, slowing it down and making it less profitable, would allow mission driven developers, community land trusts, and residents the ability to compete with cash investors. Foreign experiments like British Columbia’s Speculation and Vacancy Tax deserves exploration.

- Shift the incentives: Let’s face it, if the margins keep property flipping and deconversions profitable, they will continue. If we are serious about preserving the stock, the incentive structure needs to shift. Increasing the cost of flipping through deconversion or demolition fees, perhaps linking the fees to the cost of producing an equivalent rental unit in the same neighborhood, is one option. One for one replacement and no net loss policies are another way to shift the incentive structure.

Preventative action is needed if we want to keep history from repeating itself. Due to the diversity of Chicago’s housing market and building types, one sized solutions to the housing impacts of the pandemic may bypass huge swaths of the city. And preserving this stock is far less expensive than producing a new unit (affordable or not), so there are cost savings alongside anti-displacement benefits to preserving this stock as well. Now is the time to act and take the preservation of this critical affordable housing stock seriously.

Miriam Zuk is a Senior Program Director with Enterprise Community Partners. Diane Limas is Board President of Communities United. Charisma Thapa is Lead Housing Organizer at Communities United. Andy Geer is VP & Chicago Market Leader for Enterprise Community Partners.

[1] In 2008, 37% of low-income renter households, defined as households earning less than 80% of Chicago’s median income ($57,200), lived in rentals in buildings with two- to four units. Source: IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

[2] To estimate the number of affordable non-subsidized housing units (often referred to as NOAH – naturally occurring affordable housing), we set the affordability level at that 30% of household income for a household making 80% of the city’s median income ($57,200) or less. This monthly rent comes out to $1,144. In 2018 we estimate that 236,000 low income households lived in units with “affordable” rent. Of these, 88,000 lived in two- to four-flat buildings.

[3] Documentation often required to prove the existence of a rental unit, which informal rental units may not

[4] Deferred maintenance, due to lost income from COVID19, could result in a decrease in the value of a property and higher risk of flipping or vacancy – in stronger markets investors may be able to get units at a lower price due to deferred maintenance and flip them for a profit. In weaker markets, an owner may sell at a low price to an investor that sits on the property, leaving it vacant until “the market picks up” while it remains cheaper to keep it uninhabited.