An environmental justice collaborative in the Southeast Chicago—Calumet Connect—has been working to understand the lasting health impacts of industry in their community. Chicago urban planning did not historically consider human health impacts, and in the Calumet River area, it is time for a revamp

By Christina Harris and Olga Bautista, Alliance for the Great Lakes

By Christina Harris and Olga Bautista, Alliance for the Great Lakes - February 4, 2021

What springs to mind when you picture the 26 designated industrial corridors in the city of Chicago? Factories, aggregate piles, housing, warehouses, railyards, light manufacturing, retail, and commercial spaces?

There is no one image of what industrial corridors look like or what type of activities happen within them. They are all different, and many are currently going through a process of change thanks to the City’s Industrial Corridor Modernization Initiative, which has been planning for each corridor’s future, beginning with an evaluation of the North Branch Corridor in 2016. These planning efforts are needed to tackle the challenges that linger within legacy industrial corridors, such as the Calumet Industrial Corridor, which were developed without attention to public health. As a result of past decisions, residential and industrial areas today are situated close to one another without appropriate buffer areas. Housing is just blocks away from smokestacks—the devastating consequences of which are on display in the aftermath of the Hilco demolition in Little Village.

So, what are the lasting health impacts of Chicago’s industrial corridors? What are the long-term consequences of inadequate planning decisions that did not consider human health, particularly in communities of color? Policies that designated these corridors had inequities built into them and, by extension, they still persist in our daily environments. The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) released the Cost of Segregation in 2017 to articulate the impact on Chicago residents quality of life, while still grappling with the lasting effects of racial and economic segregation. Legacy industrial corridors are a manifestation of this toxic and continuing history. Hilco made headlines, but everyday environmental injustice still goes unreported.

The Calumet Connect Industrial Corridor Working Group—an interdisciplinary stakeholder group made up of Southeast Side residents, as well as organizations like the Southeast Environmental Task Force, Alliance for the Great Lakes, and many others, including MPC—has been collecting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data to determine the public health impacts of industrial land use in the Calumet Industrial Corridor. Funded in part by The Chicago Community Trust’s Our Great Rivers grant, this collective has been hard at work for the past two years with the overall aim of informing the City’s Industrial Corridor planning process for the Calumet. This working group is a true display of “people power,” with stakeholders, collaborators, residents, and partners coming together to gather and report on public health information that often goes uncollected.

Below are a few highlights detailing these efforts—which will be explored in-depth as part of a continuing blog series—as well as the implications of our findings, especially in light of the ongoing novel coronavirus public health crisis.

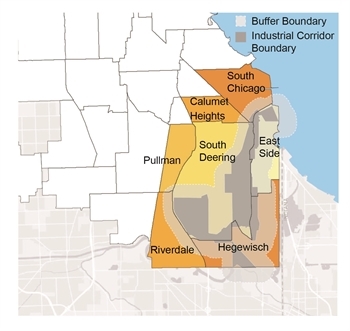

Figure 1

Define the community

In collecting this information, the working group first set an overall project boundary to begin establishing its “universe” of information. The boundary includes all of the Calumet Industrial Corridor as well as a buffer distance of a half-mile. Figure 1 identifies the community areas and geographic extent included within our study area.

Examine the impact of industry

The working group began by mapping the location of all industrial facilities within the study area relative to their surrounding land uses (residential, commercial, etc.) The goal was to determine to what extent these industrial land uses could pose negative health impacts on community residents and workers. For the purpose of our analysis, we focused on the land uses in the quarter-mile surrounding each industrial facility.

Our exploration revealed that the level of risk on human health presented by any one facility can be captured through a variety of different tools and datasets, most maintained by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Two important tools for understanding risks are:

- The Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program [1] aggregates data from sites where reportable releases have occurred. TRI sites are facilities that have reported on- or off-site toxic chemical releases in quantities outlined by the EPA’s official program.

- The Risk Screening Environmental Indicators Model considers every Toxic Release Inventory facility’s release in terms of the size of the chemicals, the size and location of the exposed population, and the chemical’s toxicity. A high score highlights releases that would potentially pose greater risk over a lifetime of exposure, and a low score indicates low potential concern from reported TRI sites.

In reviewing site locations and land use over time, we found that the number of sites required to report under the Toxics Release Inventory Program and/or Superfund Program has decreased over time from 17 sites in 1990 to nine sites in both 2016 and 2017. Despite this, almost half these sites (a total of seven), on the 1990 TRI list also appeared on either the 2016 or 2017 TRI list. These companies include Atlas Tube, American Zinc, Cargill, Ford Motor Company, PPG, PVS Chemical, and Sherwin-Williams. Repeated appearance on this list suggests long-term contamination and repeated toxic exposures for both workers and residents living in proximity. However, in order to understand the full picture, we also reviewed each facility’s Risk Screening Environmental Indicators score.

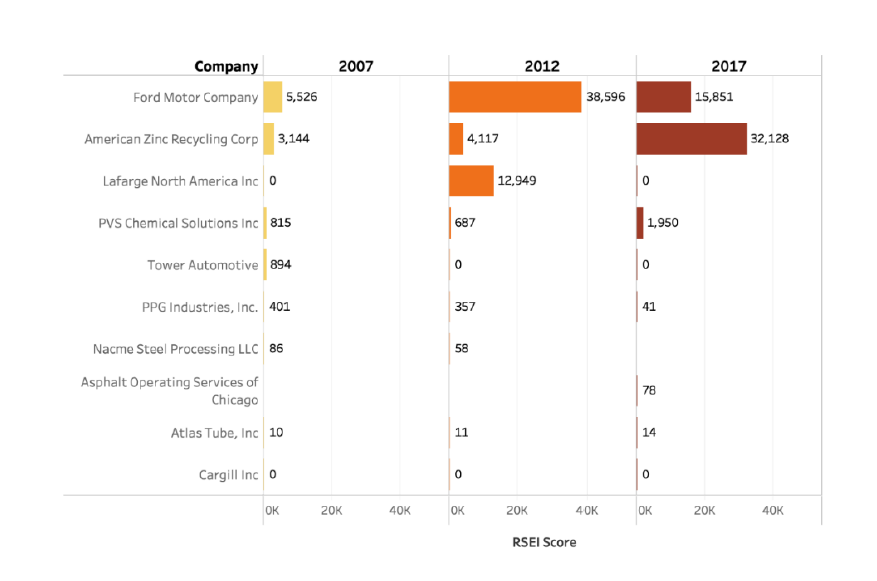

Figure 2

The working group gathered Toxic Release Inventory data and off-site release information from 2007, 2012, and 2017 for every facility in the study area [2], and created a diagram displaying the “top 10” facilities with releases over the three-year span, by Risk Screening Environmental Indicators score. These scores are indicated in Figure 2.

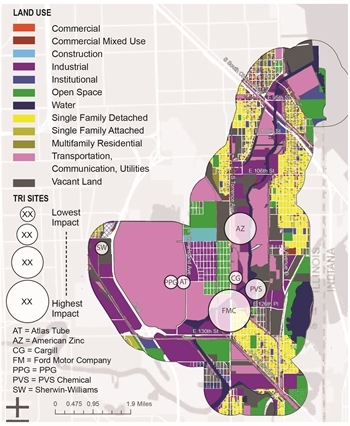

We then matched the most recent year’s scores to the seven habitual offenders identified as Toxic Release Inventory sites, and created a diagram that locates these facilities and their adjacent land uses. This resulting map accounts for each of the facility’s corresponding Risk Screening Environmental Indicators score, as seen on Figure 3. American Zinc and Ford Motor Company had the highest 2017 Risk Screening Environmental Indicators scores of the seven sites.

Figure 3

As Figure 3 indicates, only two sites are within a quarter-mile radius of residential land uses, but these adjacencies are not enough to quantify risk. A gaseous chemical release of the “right” toxicity, combined with a strong wind pattern can mean that an industrial site not immediately next to a residential land area, open space, or a commercial corridor can still cause harmful health impacts to residents and workers across the larger area. That means that chronic offenders like the Ford Motor Company, which is near residential land uses, and American Zinc, which is not, could both have significant impacts on community health. [3]

In terms of how these toxic releases “level up,” our research strongly indicates that these industrial land uses, and facilities have generated large impacts on resident and worker health cumulatively over time.

Map the inequities

Initial findings from our quantitative data collection have taken on new urgency as we consider the additional challenges brought on by COVID-19. In communities like the Calumet that already have a greater concentration of industrial facilities that contribute to land and air pollution, there is a high susceptibility to contract the coronavirus due to the high prevalence of underlying chronic health conditions. As reported by the Chicago Tribune, Chicago was one of the only cities in the United States to not experience less pollution and cleaner air during shelter-in-place, primarily due to continued freight operations and the movement of diesel vehicles. These realities, especially in the Calumet, are not going away in the near-future, and are only exacerbated during the pandemic.

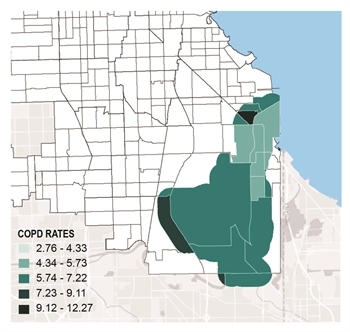

Many residents in the study area have chronic underlying health conditions, as is particularly the case for coronary heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—both flagged by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in recent months as exacerbating the likelihood of suffering severe complications from COVID-19.

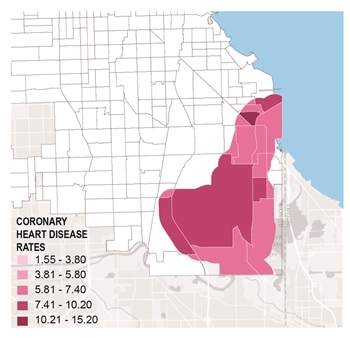

Figure 4

We mapped rates of adult COPD at the census tract level within 1) our study area, 2) eight “comparison corridors” [4], and 3) the city of Chicago as a whole. Our summary statistics indicated that the average tract-level rate of COPD in our study area was significantly higher than in the other comparison areas, as well as the “average” city census tract. This was also the case when we mapped rates of adult coronary heart disease [5]. These rates are spatially represented in figures four and five.

Figure 5

COPD and coronary heart disease are both chronic diseases prevalent in many Chicago communities, but most often seen in majority-Black and Brown communities, like the Calumet. Our environment influences up to 80 percent of our health, and industrial corridor communities like the Calumet were not planned with a focus on thriving public health and quality of life.

What would the community look like if planners valued the public health of these residents and workers, while simultaneously allowing for clean and safe jobs and responsible, equity-centered development? These are the questions that should be at the forefront as Chicago undertakes new planning processes that tackle land use changes within the city’s industrial corridors. The Calumet Industrial Corridor Working Group and this blog series will continue to raise these issues throughout 2021.

Former MPC Research Manager Shehara Waas was the primary researcher and contributor for this Data Points piece.

Read the rest of the blog posts in this series: second blog, third blog, fourth blog, fifth blog, sixth blog.

[1] EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory Program applies to companies employing 10 or more full-time employees, and regularly participates in the “use, manufacturing, or processing of toxic chemicals.”

[2] Including facilities in the study area that did not have any releases, but were still required to report use information to the EPA.

[3] The working group identified numerous instances in which considering a facility’s Risk Screening Environmental Indicators score provided valuable context for interpreting the Toxic Release Inventory release information we had been collecting. For instance, our 2012 data collection records identified that LaFarge North America Inc was on the lower end of toxic chemical releases, at least in terms of total poundage of chemical released by each facility. However, even its 850 pound chemical release—seemingly inconsequential, when compared to multi-thousand pound releases from companies like Safety-Kleen Systems or Ashland Chemical—posed a considerable degree of risk to resident/worker health.

[4] It should be noted that the eight comparison industrial corridors were chosen based on the share of land within each that is zoned for the planned manufacturing district (PMD). In the Calumet Industrial Corridor, 73 percent of the land area is zoned for the PMD, so we only chose to compare health metrics in our study area to corridors that had 73 percent or more of their land area zoned for the PMD.

[5] Both sets of data came from the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and were from their 2013 survey—the most recent year of data that was available to us.