In Atlanta, increases in median income over the past 20 years have been spread across the city's racial groups. In Chicago, by comparison, black residents have been shut out of that upward mobility. But the story is complex.

Flickr user Ethan Trewhitt (CC)

A stretch of Atlanta's BeltLine, a transformative development that has both been an engine of economic development and spurred fears of displacement.

By Shehara Waas and Vivek Ramakrishnan, Research Assistant

By Shehara Waas and Vivek Ramakrishnan, Research Assistant - February 8, 2018

Fresh off our Cost of Segregation learning trip to Atlanta in December, we had a burning question: how did the economic growth that Atlanta experienced from 1990 to 2010 play out across different racial groups, and would these same trends hold true for Chicago?

What we discovered was sobering. No majority-black neighborhoods in Chicago experienced a substantial rise in median income from 1990 to 2010, while well more than half of neighborhoods that did so in Atlanta were majority-black.

We crunched the numbers using the mySidewalk Census data aggregator, and found that out of the 31 neighborhoods within the city of Atlanta that experienced an increase in median income of over 50 percent, 20 (64.5%) were majority-black neighborhoods. This is the same percentage—65%—that majority-black neighborhoods represent out of total neighborhoods in Atlanta. In comparison, of the 20 neighborhoods that experienced an increase in median income of over fifty percent in Chicago, none were majority-black.

Let that sink in.

Atlanta struggles with its own issues of equity and inclusion. Still, MPC's staff were curious to learn from the Georgia capital's unique experience to inform progress towards equity in Chicago. Late last year, MPC organized study trips to Atlanta and Seattle to inform the second phase of our groundbreaking Cost of Segregation project. Local partners across business, government, and community organizations joined us for these study trips which were generously underwritten by Enterprise Community Partners, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, and the Ford Foundation. Atlanta was chosen because our research uncovered that, relative to the other 99 areas of study, the Atlanta commuting zone experienced one of the largest decreases in its levels of black-white segregation during the study period (1990-2010). In contrast, Chicago remained in the top 10 most segregated areas of study during the same period.

Despite its drop in segregation and overall economic growth, as our colleague Lynnette McRae articulates in her recent blog post, What I learned in Atlanta about equity and inclusion, we know that some populations in Atlanta are still being left behind.

Our analysis went on to show that of the 70 neighborhoods in Atlanta during our study period that experienced a decline in median income larger than 50 percent between 1990 and 2010, 82.3% of these neighborhoods were majority-black. So while economic growth was occurring uniformly across Atlanta neighborhoods irrespective of race, the neighborhoods that disproportionately experienced significant steps backwards were majority-black.

These numbers are thrown into sharp relief when we consider the counter-point: of the neighborhoods within Atlanta that experienced the most growth in median household income, most were high-income, majority-white areas on the north side, such as Arden Habersham, Wyngate, and Brandon.

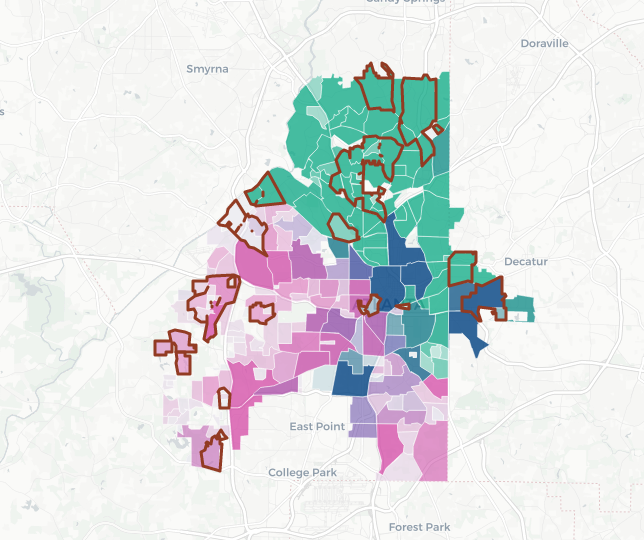

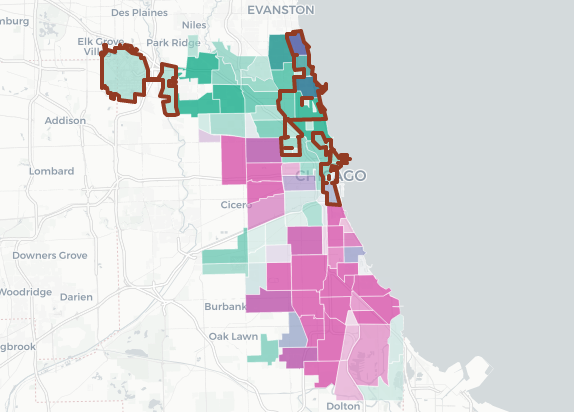

Consider the maps below, depicting Atlanta and Chicago neighborhoods according to racial density. The more pink the neighborhood, the higher the black-resident concentration, and the more green the neighborhood, the higher the white-resident concentration. Blue neighborhoods represent areas lacking a clear racial majority. Neighborhoods outlined in red are those that experienced median income gains of over 50 percent during our 1990-2010 study period.

While both pink and green neighborhoods on the Atlanta map display the red outlines indicating significant gains in median income, we only see red outlines indicating income gains on the Chicago map for green (i.e., majority-white) neighborhoods.

mySidewalk Census Data Aggregator

Atlanta neighborhoods that experienced the largest gains in median income (greater than 50 percent) between 1990 and 2010

mySidewalk Census Data Aggregator

Chicago neighborhoods that experienced the largest gains in median income (greater than 50 percent) between 1990 and 2010

It is clear from the Chicago map that exceptional economic growth seems to have been predominantly a downtown and North Side phenomenon over the two decades.

And it's even more clear from both maps that the two cities had vastly different stories of income growth over the two decades. But both Chicago and Atlanta struggled (and still struggle) with some of the unintended consequences of exceptional economic growth, and the harm that can result to communities of color.

Predominantly Latino/a community areas in Chicago such as the Lower West Side and Logan Square have experienced large increases in rent and subsequently, displacement. MPC is currently exploring the development of a tool that could help Chicago communities analyze the likely impacts of proposed investment and better equip stakeholders and government leaders with strategies to anticipate and proactively manage neighborhood change more equitably.

Unlike in Chicago, where Sampson and Hwang (2014) found that neighborhoods that are more than 40 percent black do not gentrify, many historically black neighborhoods in Atlanta that are shown to have significant gains in median income—such as Kirkwood, East Atlanta, and the Old Fourth Ward—are all cited currently as high-risk areas for displacement.

Atlanta's West Side, comprised of English Avenue, Vine City, Atlanta University Center, and Ashview Heights experienced a 64 percent decline in median income, from $58,527 to $21,014. Suburbanization in the 70’s drained the area’s vitality, with vacancies facilitating crime and catalyzing the descent into poverty. Though many West Side revitalization attempts took place in the mid-90’s, they have not appeared to influence income levels significantly for this area of Atlanta.

Due to the seemingly uniform growth of all communities in Atlanta, the ones that desperately need resources, job opportunities, and revitalization can be overlooked. Many success stories do exist, however, and Chicago policymakers can take note of some of the region’s catalytic developments. The surrounding census tracts of Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson Airport (which falls just outside the municipality of Atlanta), for instance, experienced an aggregate 29.51 percent increase in median income from 1990 to 2010. These disparities were part of the reasoning for building the Atlanta Falcons Mercedes-Benz Stadium, a $1.5 billion development on Atlanta's West Side as a "catalyst for change".

Keisha Lance Bottoms, Atlanta’s newly inaugurated mayor, has been a strong proponent of inclusive economic growth, centering her platform around the “All Rise” program which emphasizes growing small businesses, pursuing inclusionary zoning for new developments, and requiring hiring standards for publicly-funded projects to prioritize communities that most need jobs.

Some of these efforts are already underway in Chicago, but there is much more to do on the pathway to inclusive growth. In a city that is significantly more segregated than Atlanta and faces the dual problem of slow growth and uneven growth, it is necessary to make informed revitalization and development policies that benefit everyone. Strong moves in recent years include Mayor Emanuel's Neighborhood Opportunity Fund, which channels fees from booming central area neighborhoods to support economic development in struggling areas, and inclusionary housing pilots that require more than 10 percent affordable units on-site. MPC's forthcoming Phase II report of the Cost of Segregation will articulate additional policies to support equitable development for all communities throughout Chicago.

MPC's learning expeditions to Seattle and Atlanta were made possible through the generous support of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Enterprise Community Partners and the Ford Foundation.

Learn more about MPC's Cost of Segregation-related research trips to Seattle and Atlanta: